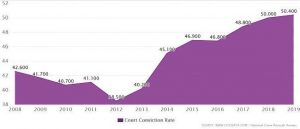

The conviction rate in ACB cases in Maharashtra has dwindled to 18% in 2019, indicating that in 82% of cases, culprits go scot-free. This endangers the democratic rights of honest citizens. It also amounts to a colossal waste of time and resources of the State. Pan India, Maharashtra remains on the top in registering cases against the corrupt, but the conviction rate is far from satisfactory. It is not only officers from the ACB but anyone interested in promoting the democratic human rights of citizens and associated with the criminal justice system that needs to pay serious attention to improving the conviction rate against corrupt public servants.

On the other hand, in Gujarat, the conviction rate against the corrupt is above 40%. There are many other States whose performance is better than Maharashtra. It is, therefore, proposed that we need to address this issue based on the following points:

Effective steps need to be ensured at various levels, including complainants, witnesses, investigating officers, FSL officers, sanctioning authorities, prosecutors, and judicial officers. Separate measures also need to be taken at the departmental level through a Departmental Enquiry.

Based on my experience as DG ACB, I propose to explain these as under:

Complainants: After a successful trap, complainants are worried about their work in the government office. Investigation officers of the ACB need to look at the complainant’s work as it were their own and follow it up with the concerned government office till completion. Writing a letter to this effect to the officer-in-charge of that department is very effective.  This would create confidence in the minds of the complainant about the trustworthiness of the ACB. Secondly, to ensure complainants do not come under pressure from perpetrators and their colleagues, it is necessary to organise a meeting with these complainants from time to time and boost their morale till the case stands in court. Thirdly, before the case comes up in court, there should be a rehearsal to refresh the complainant’s memory about the actual happenings and various actions taken before and at the time of the trap.

This would create confidence in the minds of the complainant about the trustworthiness of the ACB. Secondly, to ensure complainants do not come under pressure from perpetrators and their colleagues, it is necessary to organise a meeting with these complainants from time to time and boost their morale till the case stands in court. Thirdly, before the case comes up in court, there should be a rehearsal to refresh the complainant’s memory about the actual happenings and various actions taken before and at the time of the trap.

Witnesses: These are government servants. They should be less than 45 years old when called for a trap. In cases where they turn hostile, concerned departments should be asked to initiate action against them.

Witnesses: These are government servants. They should be less than 45 years old when called for a trap. In cases where they turn hostile, concerned departments should be asked to initiate action against them.

Investigating Officers: Training at the time of induction, refresher training courses in identifying complainants, procedures, using new gadgets and technology is essential for investigating officers. We often observe that when cases come up before the court, the investigating officers attached to these cases are untimely transferred. They must be invariably released and attend these cases in court promptly. Incentives to officers who conduct investigations resulting in a conviction should be encouraged.

FSL Officers: Expert opinion, particularly in voice samples by FSL officers, is necessary. Delays seriously hamper prosecution. Trained staff with adequate technology should be readily available. These should be regular employees and not contractual workers as they would not be available when needed in courts for evidence.

Sanctioning Authorities: When investigation reports are received by the sanctioning authorities, they should be confident to discern whether it is a prima facie case and not waste time in scrutiny, which would anyway be done by judicial officers. Sanctions should be provided within a maximum of two months. Many of these officers give evidence by video conferencing to the court. However, the quality of these videos is quite poor, which often results in acquittal. The same needs to be improved.

Sanctioning Authorities: When investigation reports are received by the sanctioning authorities, they should be confident to discern whether it is a prima facie case and not waste time in scrutiny, which would anyway be done by judicial officers. Sanctions should be provided within a maximum of two months. Many of these officers give evidence by video conferencing to the court. However, the quality of these videos is quite poor, which often results in acquittal. The same needs to be improved.

Prosecutors: Lack of interest by prosecutors is a major hassle in preventing convictions. Training needs to be organised for prosecutors at least once in six months for them to appreciate technological innovations in investigation and project these effectively.

Prosecutors: Lack of interest by prosecutors is a major hassle in preventing convictions. Training needs to be organised for prosecutors at least once in six months for them to appreciate technological innovations in investigation and project these effectively.

Judicial Officers: Though the Hon’ble High Court has directed ADDL District Judges be declared as special judges to complete at least five ACB cases, these are hardly implemented, resulting in inordinate delays; with cases ending in acquittal. Training  courses are also necessary for judicial officers at district levels to enable them to be aware of new judgments by the Hon’ble Supreme Court and Hon’ble High Courts. Technological innovations also need to be brought to their notice so that they can appreciate these as well. Instances where judicial officers keep acquitting the accused need to be brought to the notice of the Hon. Chief Justice of the High Court with a personal meeting once a month.

courses are also necessary for judicial officers at district levels to enable them to be aware of new judgments by the Hon’ble Supreme Court and Hon’ble High Courts. Technological innovations also need to be brought to their notice so that they can appreciate these as well. Instances where judicial officers keep acquitting the accused need to be brought to the notice of the Hon. Chief Justice of the High Court with a personal meeting once a month.

Immediately after the traps, departmental proceedings must be initiated to avoid administrative lapses they must be completed expeditiously. After conviction, it is necessary to weed out these convicts after issuing a written notice to them.

Immediately after the traps, departmental proceedings must be initiated to avoid administrative lapses they must be completed expeditiously. After conviction, it is necessary to weed out these convicts after issuing a written notice to them.

In addition to the above, it would be desirable that each case is scrutinised by legal interns associated with a nearby law college. Defects in the investigation can be eliminated with their help at the initial stage itself.

Implementation of the above measures and supervision from the higher levels would improve the conviction rate.

I hope that all concerned would take note of these suggestions.